How to Open a Restaurant as a Newcomer to the USA

Two restauranteurs spoke on a recent podcast about bringing unfamiliar concepts and cuisines to the United States.

Opening a restaurant is hard. Opening one as a newcomer in a new country is something else entirely.

Through the stories of two immigrant restaurateurs — Svitlana Edie, from Ukrainian, opening Slava, a cafe-bakery in downtown Asheville, NC and Anesh Bodasing, the Indian-Canadian-South African founder of Tiffin Box, a fast-casual Indian concept in Florida — you can see behind the scenes of restaurant ownership for newcomers.

Edie's and Bodasing's paths are wildly different.

Edie came from rural Ukrainian roots to Asheville, NC.

Bodasing has a background in car dealerships in Canada to the Hard Rock Cafe in Cape Town, South Africa, and now owns restaurants in Tallahassee and soon to be Gainesville, FL. But the principles underneath look surprisingly similar.

Here are seven ideas from their stories to sit with if you’re thinking about opening a restaurant in the U.S., especially as a newcomer.

1. Your first asset isn’t your menu. It’s your story.

Food matters. But for both Svitlana and Anesh, the story behind the food is the real engine.

Svitlana isn’t opening Slava just to sell borscht and cabbage rolls. She wants to recreate the kind of communal life she grew up with — where you could walk into any neighbor’s house and belong. She expressed wanting her cafe to be a place where people talk to each other and share both “the hard things and the good things” in the heart of downtown Asheville.

As she puts it, “Every item on the menu… has some kind of story,” right down to her grandmother’s cabbage rolls.

Anesh’s “why” is different but just as intentional. For twelve years before Tiffin Box opened, he ran a one-question survey to the people he met:

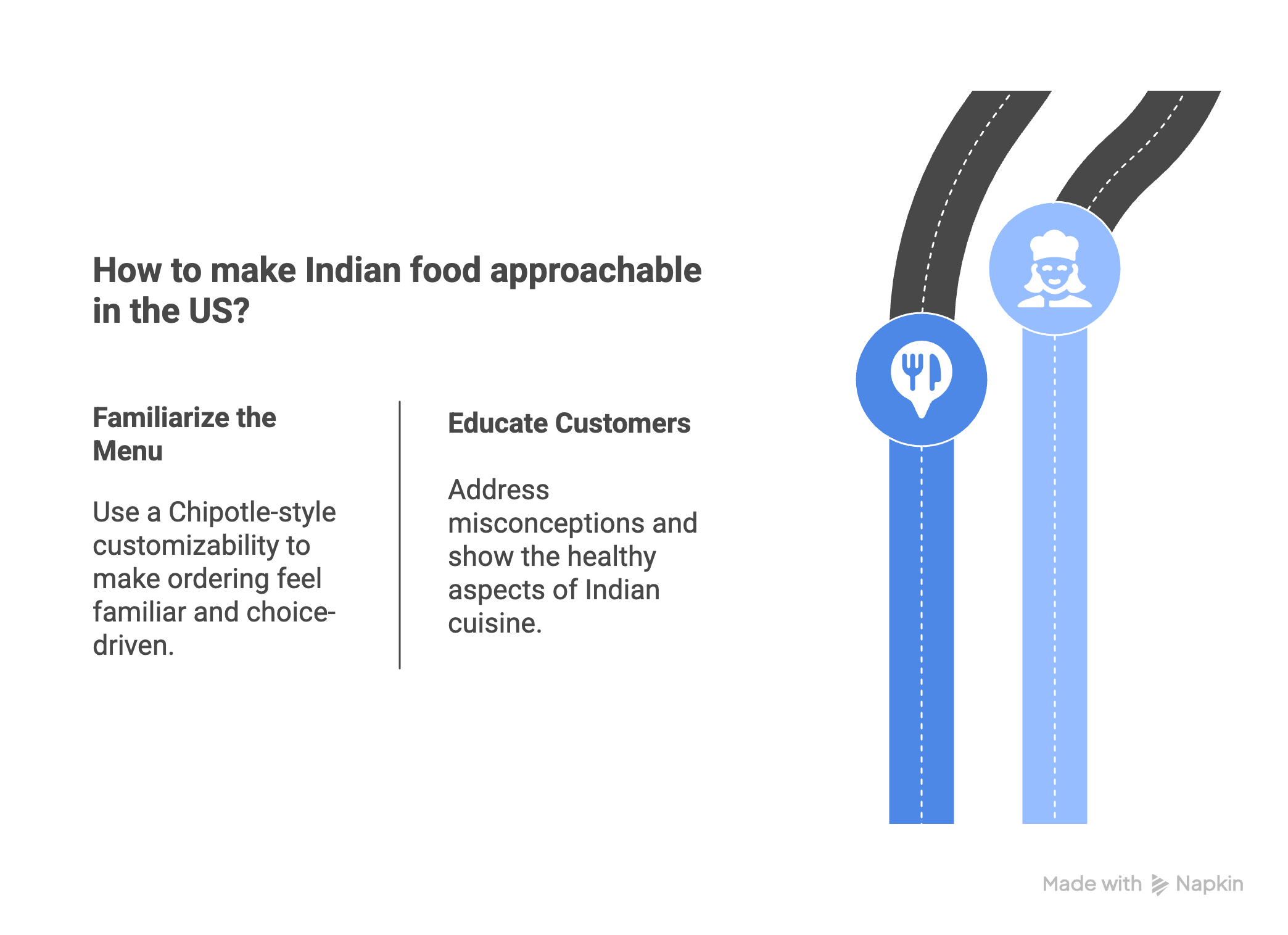

“Have you ever had Indian food?”

He heard the same patterns over and over:

- Loved it, but never went back — I don’t know what to order.

- Never tried it — it’s oily, spicy, I’ll get an upset stomach.

Tiffin Box is his answer to that story: a Chipotle-style line that makes Indian food feel familiar, choice-driven, and approachable.

Thought starter:

What's the why for your concept? What's going to intrigue people who might not be familiar with your cuisine?

2. Grit starts long before the lease is signed.

The hustle doesn’t start when the contractor shows up. It starts years earlier.

Svitlana grew up on a small self-sustaining farm in a Ukrainian village. When she reflects on why she can handle the grind now, she doesn’t talk about business books; she talks about her grandmother:

“Growing up hard work was not something you even thought about. That’s the norm. It’s just part of life I guess.”

When she immigrated, she didn’t speak a word of English. So she did whatever she could: dishwasher, prep cook, server, banquet captain, bakery work, accounting, management — often working three jobs while going to school and learning the language.

She calls that her advantage as an immigrant:

“I didn’t have a choice. I had to adapt to my environment… do whatever I needed to do.”

By the time she’s negotiating leases and dealing with inspectors, the muscle for “do what you have to do” is already built.

Anesh’s grit was shaped differently — by decades in hospitality around the world, and by constantly reinventing his life across continents. But the emotional pattern is similar: each move, each job, each setback was another rep in the “adapt quickly or lose” training.

Svitlana used a great phrase in her conversation with Wil: "experience assets." Her upbringing, the difficult process of immigrating with no money and no ability to speak English, these gave her experience assets to contribute to her resilience today.

Thought starter:

What "experience assets" do you have that you've not considered as asset yet? What difficulties or challenges have you learned invaluable lessons from to apply to your business?

3. Opening is a multi-year marathon, not a ribbon-cutting.

On Instagram, “Opening Soon” looks like a few cute build-out photos and then a soft opening party.

In real life?

For Svitlana, the dream of a cafe started around 2019. Then COVID hit. Every wedding and event on her catering calendar vanished in 2020. She paused, leaned on a full-time job to survive, and waited until events picked back up in 2021 before she could seriously look for a space again.

Then came the search itself. She spent years touring locations:

- Many spaces were too expensive to build out.

- Others had kitchens that simply didn’t fit the kind of baking and food she does.

- She finally found her Wall Street space in 2025, nearly four years after she originally started looking.

And once she signed?

- Plumbing had to be completely ripped out and replaced — concrete slab cut, pipes pulled and redone.

- Permitting dragged.

- She had to replace her electrician mid-stream.

Delays continue to stack up, and her opening date is getting pushed further and further down the line. Her response?

“It just is what it is. I’m just taking it one day at a time and doing what I need to do to continue making progress.”

Anesh’s timeline isn’t shorter. He thought about Tiffin Box for 12 years before opening. Then it took almost two years just to find a landlord willing to take a risk on a fast-casual Indian concept that no one understood yet.

And he opened in late 2019 — right before the pandemic “pulled the floor out from under his feet.”

Thought starter:

Could you handle your dream taking five to fifteen years to materialize — with detours, pandemics, and plumbing trenches in between?

Anesh told Wil regarding this difficult phase:

"Let me tell you, you're dying to get to that opening date because until that opening date, the money is only going one way – out the door. So you're thinking, 'we got to get this place open.'"

4. Capital, cash flow, and the calculus of risk.

Here’s the unsexy truth: capital is hard to access sometimes. Even more so, the restaurant business is notoriously risky, and even more so when you're introducing an unfamiliar, independent concept.

Svitlana is blunt:

“No bank is just going to give you the money to do it.”

She and her husband slowly built equity by buying a home in 2009, building another, selling it, and rolling that into their position. Eventually, she was able to take out a HELOC — a loan against her house — to finance the cafe, and only recently secured a small seed loan tied to the Small Business Administration.

“It took a lot of planning and a lot of time to get to that point… It doesn’t just happen overnight.”

Anesh describes his first store this way:

“The first restaurant was blood, sweat, tears, maxed out credit cards… and high interest rates.”

And while everyone loves to talk about “being your own boss,” Anesh points at the part you don’t see about the early pre-cash flow stages:

"When you’re making a $9,000 check out to the sign guy or a $14,000 check to the plumber, it hurts.”

His mentor boiled the whole thing down to two words that haunt every owner:

“There’s two words that everyone thinks at some point… cash flow.”

Thought starter:

How much access to capital do you have and what is your risk tolerance?

5. Being an outsider can be your unfair advantage.

Both Svitlana and Anesh experience being outsiders — culturally, linguistically, conceptually — not just as a handicap but as a superpower.

Svitlana says something quietly radical:

“I have an advantage as an immigrant being able to overcome challenges because I had to be adaptable… work three jobs… going to school and learning English. It became part of the norm.”

Her philosophy is brutally simple:

“If you want something, you don’t just talk about it. You have to do something about it."

Anesh’s “outsider” advantage is more about concept than country. Fast-casual Indian is both his greatest strength and his greatest weakness:

“Our greatest strength is we are a fast-casual Indian restaurant.

Our greatest weakness is we are a fast-casual Indian restaurant.”

The same thing that attracts adventurous guests repels others who still associate Indian food with “oily, really spicy, upset stomach, don’t like the smell.”

Instead of whining about that, he leans into education, simplification, and a familiar service model. He accepts that being different means he has to work harder and that it gives him a lane with very little competition.

Thought starter:

What might be asset that you've considered a liability? Like Anesh's unfamiliar concept, can be just as (or if not more) positive that negative?

6. “Never give the guest a reason to complain.”

Once the doors open, the grit shifts from survival to standards.

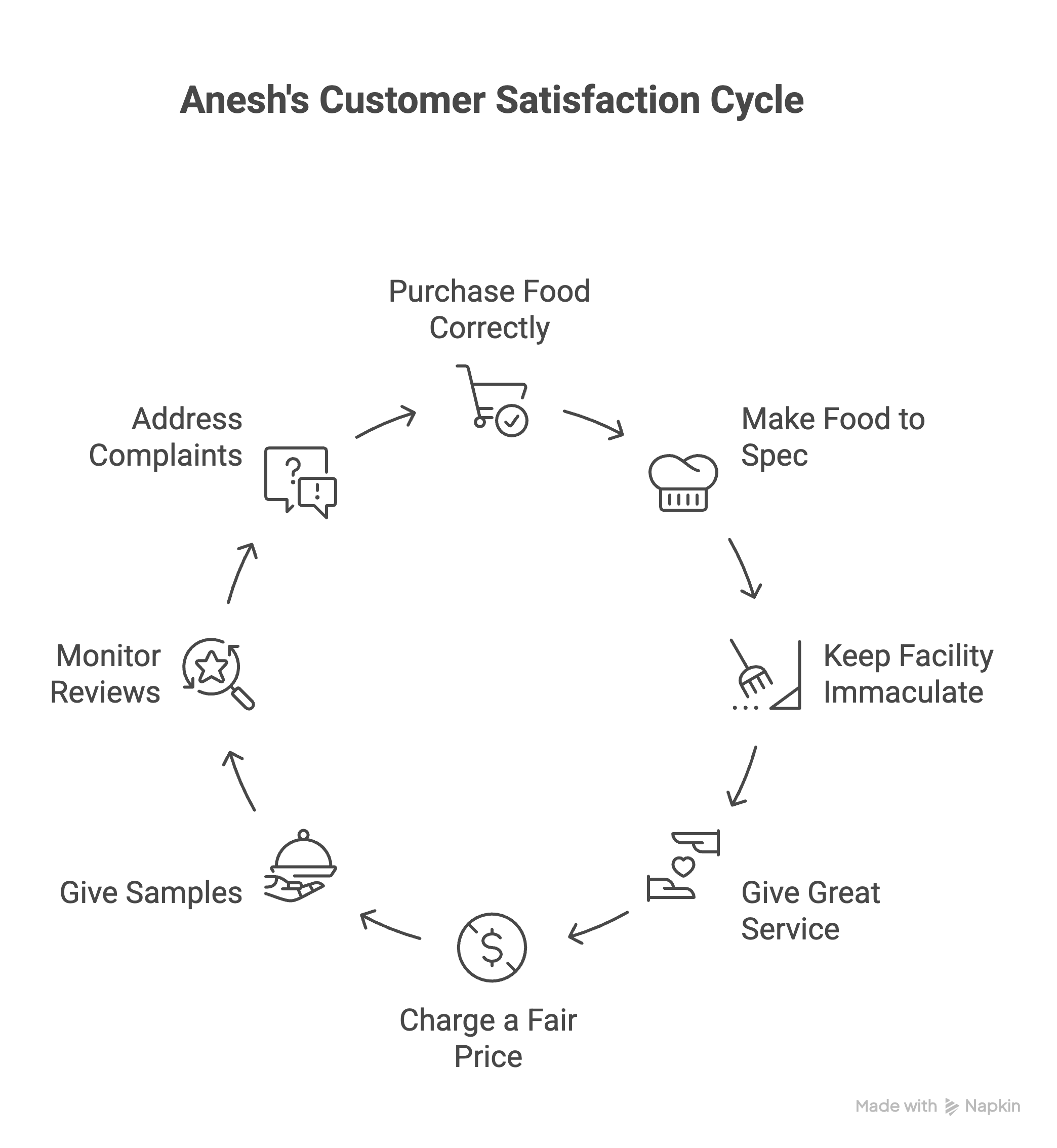

Anesh has a mantra for his team:

“Let’s never give the guest a reason to complain.”

Then he breaks it down into six very unglamorous basics:

- Purchase food correctly.

- Make the food to spec.

- Keep the facility immaculate.

- Give great service.

- Charge a fair price.

- Always be giving samples.

If they do those six things, he believes “there is no reason whatsoever we will ever get a complaint.” And when a three-star review does show up?

“There’s a very, very strong possibility we dropped the ball… If one person complained, that means 10 or 15 other people just aren’t saying anything. They’re just never coming back.”

He posts his cell number publicly on platforms like Google and Yelp and invites guests to call him directly. No hiding, no defensiveness — just accountability.

Svitlana’s version is gentler but just as demanding. Her standard is about emotional hospitality: designing a cafe where people feel safe to talk about “the hard things and the good things.” If the room doesn’t feel like that, she hasn’t hit the mark.

Thought starter:

Could you write your own “six basics” on a napkin? Would your staff know them? And do you tell the world, out loud, that if you drop the ball, they should come straight to you?

7. You may be the founder, but you won’t do this alone.

One of the quieter themes in both stories is how many people are woven into a single restaurant opening.

Svitlana points to friends, colleagues, her current employer, her family:

“Even getting here, I wouldn’t have been able to do it all on my own… There’s a lot of people I give credit to for helping me get to this point.”

She’s not just hiring random staff either. Her mother and sister will be by her side in the kitchen — a practical move, but also a way of baking family into the daily operations.

Anesh’s journey is basically a highlight reel of relationships paying off across borders and decades:

- A banner in Cape Town leads him to Hard Rock Cafe.

- A Hard Rock connection later opens doors in South Florida.

- Another connection in the UK gets him a GM job over the phone.

- Old bosses bring him into growing concepts; new partners give him opportunities to lead.

Thought starter:

Who is in your camp that you can lean on for inspiration, accountability, and motivation?

Conclusion

Opening a restaurant is never just about recipes or design.

For owners like Svitlana Edie and Anesh Bodasing, it’s about telling their story and sharing their experiences with their guests.

Their stories don’t romanticize the process. They show years of invisible work, like learning English on the fly and chasing landlords, or explaining your cuisine over and over and carrying risk on your back while still smiling at every guest who walks in.

But they also show why people keep doing it.

There’s the satisfaction of building something that couldn’t exist without your specific story.

Summary:

- Your story is your first asset.

Guests connect to why you exist before they memorize your menu. A clear, honest story can carry you — whether that’s a Ukrainian village café in Asheville or fast-casual Indian bowls in Florida. - Grit is built long before opening day.

The journeys often involve years of hard, unglamorous work: multiple jobs, language learning, starting at the bottom in new countries and industries. That’s not a detour; it’s training. - Opening is a long game, not a launch event.

Expect multi-year timelines: dreaming, saving, searching for space, surviving, enduring build-outs and delays. The ability to “take it one day at a time and still move forward” is a core skill. - Capital and cash flow are constant, heavy realities.

Access to money may be tough. That often means using home equity, personal savings, credit cards, and living under the ongoing pressure of cash flow — long before profit appears. - Being an outsider can be an unfair advantage.

The unfamiliar public may not understand immediately, but all of it can make you stand out in the best possible way, if you embrace the role of educator and lean into what makes you different. - Relentless guest focus is non-negotiable.

Simple, disciplined standards around food quality, cleanliness, service, pricing, and accountability (“never give the guest a reason to complain”) are what keep people coming back long enough for you to survive. - You may own it, but you don’t do it alone.

Family members, mentors, former bosses, spouses, and community all show up in these stories. The stronger your relational web, the more likely you are to make it through the hardest seasons.

Comments ()